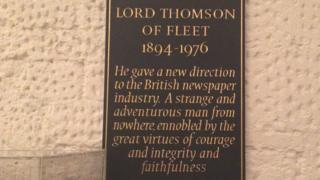

Down in the crypt underneath the vast bulk of St Paul’s Cathedral, down there where London started, there is a handsome memorial stone with a haunting inscription.

“Lord Thomson of Fleet,” it says. “He gave new direction to the British newspaper industry.”

And then the sentence that gives pause: “A strange and adventurous man from nowhere, ennobled by the great virtues of courage, and integrity, and faithfulness.”

Roy Thomson died in 1976 at the age of 82, and his was indeed a remarkable business story. The plaque made me remember it again.

He was born to a pretty poor family in Toronto in 1894, and was hindered by poor eyesight. Or maybe helped, increasing his doggedness. He dabbled in small businesses from his teens onwards, with little success.

He tried farming, and failed. He went back to Toronto and had several undistinguished jobs. Then he started selling radios in small towns deep in northern Ontario, the only territory left.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images And there began a remarkable media story. Rural radio users in the 1930s had little to listen to. So Roy Thomson bought someone else’s neglected radio licence, and his station CFCH began broadcasting in the town of North Bay in March 1931; the inaugural programme had music by the Battery Boys and a speech by the mayor.

Roy Thomson, odd job man, was on his way. In 1934 he bought a small local paper, the Timmins Daily Press, beginning what soon became a diverse media empire. By the end of the 1940s, Thomson owned 19 newspapers and was president of the Canadian daily paper publishers’ association.

But the old country beckoned. In 1952, seeking his Scottish roots, Roy Thomson moved to Edinburgh. The next year he bought the Scotsman, giving him some status but a lot of criticism as he applied commercial instincts to a venerable paper.

Then came television. The government introduced what was called, in typical British look-down-the-nose way, “commercial” television. Roy Thomson with his Scotsman credentials led the consortium which won the franchise for Scottish TV, launched in 1957.

Brash, vulgar

In a much-quoted (but maybe inaccurately quoted) phrase, he described television as a licence to print money. It was.

But print was at the heart of his increasing empire. As he put it: “I buy newspapers to make money, to buy more newspapers to make more money.”

Image copyright Gonzalo Arroyo Moreno

Image copyright Gonzalo Arroyo Moreno Like Beaverbrook before him and Conrad Black and Rupert Murdoch after him, Roy Thomson was a wild colonial boy who cut a swathe through traditional owned British newspapers.

He used the profits from STV to buy a raft of Kemsley newspapers from the Kemsley family in 1957, including the Sunday Times.

When the family owners of what used to be termed The Times of London panicked over tiny losses in 1966, Thomson was there to snap it up. His newspaper empire grew to embrace more than 200 papers in Britain, Canada and the USA, and a host of other publishing interests.

Every time he met another newspaperman, he would ask if their paper was for sale. It was brash, vulgar, persistent.

Not just publishing, either. With its Scottish perspective connection, the International Thomson Organisation (as it was by then called) joined a consortium that successfully struck oil in North Sea fields.

Much of the group’s flair was due to a canny chief executive, Gordon Brunton, now Sir Gordon. He had been at the London School of Economics with Vladimir Raitz, the man who revolutionised post war British travel.

In 1950 Mr Raitz had organised what was effectively the first modern package holiday, flying fellow Russians to Corsica for a holiday in the sun for 32 all round, at a time when harsh official limits on taking sterling abroad severely restricted foreign travel from the UK.

Mr Raitz founded the pioneering Horizon Holidays and later helped Sir Gordon launch what became Thomson Holidays, one of the main travel companies of its time.

Remarkable story

I saw Roy Thomson once, coming in through the revolving doors at the Sunday Times in London, where he moved around by public transport.

His pebble thick spectacle lenses glinted in the sun, and he was on his way upstairs to his office, probably to get out his ruler and measure the amount of advertising in his own newspapers and that of his rivals.

This overt preoccupation with the commerce of newspapers was scorned by superior journalistic types, but it was he, not they, who got a barony named after Fleet Street, where his newspapers never had offices.

Image copyright Pascal Le Segretain

Image copyright Pascal Le Segretain But for all Roy Thomson’s commercial instincts, he failed to transform the impossibly tangled way that newspapers were produced.

A year-long strike of production workers at the Times and the Sunday Times in 1979 changed little, and not long afterwards his son Kenneth (Lord Thomson in Britain, Ken in Canada) sold those two papers to Rupert Murdoch, who then took on the print unions in a decisive encounter that transformed Fleet Street.

Many other papers followed that sale. But though print has little or no part in it, Roy Thomson had created a continuing huge business empire.

At one time his late son Ken (also Lord Thomson, but only in Britain) was named by the magazine Forbes as the ninth richest man in the world.

Roy Thomson’s grandson David inherited the leadership of the company in 2006 and continued the evolution of the business by buying the venerable news agency Reuters two years later. He’s now chairman of the company named Thomson Reuters, the biggest business information provider in the world.

It is a remarkable family story, based on the man who was still a failing jack of all trades at the age of 36, still known only in Canada at the age of 54, who became a national known figure in Britain only in his 60s. Roy Thomson’s autobiography is called “After I was 60”.

That’s what the plaque means by calling him a strange and adventurous man from nowhere. It is striking to see him so memorialised in St Paul’s.